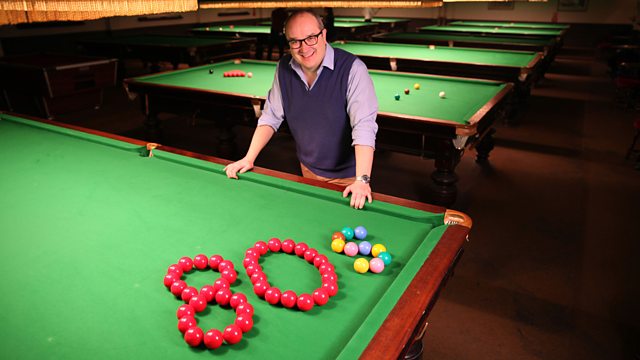

A review of Dominic Sandbrook, Let Us Entertain You – Part one: The New British Empire (first broadcast on BBC2, 4th November 2015).

Available for a limited time on the BBC iPlayer at http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b06nw1vl/dominic-sandbrook-let-us-entertain-you-1-the-new-british-empire

[This is a quickie, and the latter sections are not footnoted too well. This reflects a lack of time, and a lack of proper rigour. I would be tempted to call this a first draft and subject to revision, but I have no intention of returning to this. My advice is that if an element of this review does not have a footnote, it is done from memory with a bit a back-up courtesy of Google – and should thus be dealt with caution.]

In recent years Dominic Sandbrook has emerged as one of Britain’s leading right-wing historians. His basic method is to emphasise the continuity of people’s everyday lives. In the past he has played down the importance of popular culture. In his book about the Sixties White Heat he argued that the common people continued to tend to their gardens rather than joining in the swinging sixties.[1] Typically, he then fails to analyse the impact of gardening on people’s lives[2] or, indeed, that gardening can be an expression of radical politics.[3] His is a picture of a conservative nation, more at home with Dads’ Army than Monty Python. The problem with his view is that it does not recognise change, which as Arthur Marwick describes, starts with small groups of pioneers before permeating through society.[4]

In his new BBC2 series Dominic appears to have revised his attitude towards popular culture. This is not a programme about gardening, but about the Beatles and Black Sabbath which are now seen as part of “the extraordinary success of British popular culture in the last century”, and in turn are key to understanding what modern Britain is. Dominic has not changed his mind completely. Such popular culture has at its heart, in Dominic’s view, a reassertion of the Victorian values that once made Britain great through industry and empire, and now make it great again through Phantom of the Opera and Grand Theft Auto.

In this first programme “The New British Empire” Dominic starts to develop a number of themes:

- That while in the past Britain made things, it now makes popular culture which it exports to the world.

- The nature of the culture as conditioned by Britain’s imperial decline, but the success of this has overcome the perception of that decline (and possibly the decline itself?)

- (I would argue that to show this, Dominic uses a reductionist view of culture where it does no more than reflect the economic conditions under which it was created).

- This culture is a consciously manufactured product.

- And continues a spirit of entrepreneurship, enterprise and innovation established by the Victorians.

What I hope to show below is that this is very poor history. It commits the worst sin in the creation of a historical narrative: it confuses the order of events so causes appear later than consequences. Elsewhere evidence is one-sided, inconvenient facts are ignored and the conclusion forced onto the facts.

No longer making things, now making culture

The centre of Dominic’s argument is that Britain has ceased to be a country that makes manufactured goods, but has instead become one that makes popular culture. There are problems in the factual content that is used to support this from the very start. As the programme opens, with camera panning across the London skyline towards Stratford, Dominic states in his best authoritative voice that the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics were “billed as a showcase for the very best of British’”. Were they? By whom? When? My suspicion is that these words are from Dominic’s own imagination. They allow his facile comment this created a problem: “no-one really knew what that [the best of British] meant”. Although it is possible to find commentators using these words both to describe their aspirations for the event[5] and in praise for the event afterwards[6] this was not how the creators of the event understood it. The title of the opening ceremony was “Isles of Wonder”, and it sought to create a sense of modern British identity emerging through its history. The director of the ceremony, Danny Boyle, wished to trace British identity emerging through industrialisation, the struggle for women’s suffrage and the creation of the NHS. Of course, elements of popular culture are shot through this, particularly the music of the Beatles not to mention James Bond and Mr. Bean. If anything, the organisers worried that they had created something too parochial and inward looking, the very opposite of the outward looking showcase that Dominic claims. Although the evidence is the world (Dominic aside) got it, this was in an important sense an inward-looking opening.; as Boyle stated in the official programme, its theme was: “We can build Jerusalem, and it will be for everyone.”[7]

Dominic thinks that the opening ceremony has another meaning, that industry and empire has been replaced by popular culture – that Britain “has gone from a country that makes things to a country that makes culture” and this popular culture bestrides the globe as the Empire once did. Even though if this is not what the opening ceremony was actually about, there is some truth to the more general claim that the cultural and creative industries are important to the UK economy. The UK produce a considerable quantity of commercial cultural products (popular culture if you like), but this is blown up out of proportion by Dominic.

A British Government Department of Business, Innovation and Skills report from 2012 (part of the government’s underpowered attempt to “rebalance” the UK economy after the 2007/2008 banking crisis) found room for a half chapter on the creative industries. The report states (on rather dated figures) that in global terms the UK does have an important creative sector, its UK creative-sector exports constituted 9.4 per cent of the global total (whereas British goods and services in general constitute 6.2 per cent of global trade overall). This greater share of exports can, in large part, be explained by the strength of the computer software and gaming sector which then accounted for one-third of these exports (and has continued to grow as a proportion so today it is more like half of creative exports). While this is a significant element of the UK economy, it was worth around £16.6 billion in 2007, this constituted only 4.5 per cent of all British exports.[8] Other sectors are far more important, particularly that Britain accounts for 22.8 per cent of the world financial services. Indeed, the trade surplus (the excess of exports over imports) in financial and insurance products in 2014 was £61 billion[9] which gives a far more accurate picture of the imperial roots of the UK’s post-imperial economy. Indeed, quite contrary to Dominic’s “thesis”, many sectors of the UK manufacturing industry outperform the creative sector. Figures from 2011 show contributions from areas of manufacturing far in excess of the creative sector: pharmaceuticals were worth (£24 billion), chemicals (£29 billion), computer, electronics and optical (£23 billion), motor vehicles (£31 billion), aircraft (£22 billion), machinery and equipment (£28 billion). All far outstrip export earnings from film and video recording (£300 million), audio recording (£171 million), print publishing (£2.7 billion) and creative, arts & entertainment services (£4 billion). Even rubber products (£2 billion) were able to outstrip the export earnings from music (£1.6 billion) but few would dream of arguing that rubber goods define modern Britain.[10]

Even within the creative industries it is not the export of popular culture that dominates. The dominant “creative” exports are advertising and marketing expertise, computer software and other products that are far removed from British popular culture.[11]

It is true that the cultural sections of the UK economy are strong. Britain has the third largest market for music in the world (after the USA and Japan). It exports more books than any other publishing industry in the world (although many of these books are likely to be technical, not cultural) . It has the second highest-grossing film production in the world. It is the third largest computer game producer in the world.[12] But the cultural sector is a relatively small sector of the world economy, and while important these industries are far from defining Britain economically. Britain’s share of the world’s industrial output may have shrunk, but its exports are now dominated by the service sector, retail, banking, financial services, health services, transport, and communications and so on, not popular culture.

This does not stop Dominic claiming huge importance for popular culture in terms of the value of British exports. He thus spends some time emphasising reports of the Beatles being important for British export earnings without ever putting in context. He quotes the figure of the Beatles earnings in the US at £20 million in 1967. This would have constituted 0.05 per cent of British GDP for that year, which while impressive for one band, in itself does not make them the “prime minister’s secret weapon” or significant for the UK economy.

The culture of decline

There is thus a huge question-mark over Dominic’s next assertion: that the nature of Britain’s rise as a cultural exporter is conditioned by its imperial and industrial decline. Here he uses the example of heavy metal pioneers Black Sabbath to show that as industry declined, cultural production took its place. Dominic expressly states that in the late 60s Black Sabbath rose from “the ashes of our industrial heritage.” His narrative here is rather confused, he refers to the “steel works” of Birmingham, but the steel industry was found in Sheffield, the North East and Scotland. The West Midlands was the centre of engineering, including stamping and shaping metal. It was the foundries, where molten iron was cast for components that the dirtiest, most dangerous and unpleasant of jobs in the region were found. Dominic appears to be using the foundries of the West Midlands to stand for all industry in the area, much of which was far lighter work. Even so, to say that the members of Black Sabbath were destined for jobs in the “steel works” before “they decided their lives should be different” is wrong on a number of levels. Of the four original member of the band, only Tony Iommi worked in engineering, before the accident where he lost his finger tips, although this was one of a number of short term jobs he took as an aspiring professional musician. He had also worked as a trainee plumber, but no-one would suggest that Black Sabbath’s music was influenced by blocked U-bends. After his accident he worked in a shop for a time. Ozzy Osbourne was too much of an oik for even semi-skilled factory jobs, and mainly worked on building sites. As far as I can make out, drummer Bill Ward never had a proper job and was always a drummer. Bass player Geezer Butler was training to be an accountant.[13]

Even if all of Sabbath had been working in heavy industry, Dominic’s assertion that it spat them out onto a human slag heap is wrong. British industry may have been ageing, creaking, undercapitalised and uncompetitive but in the 1960s was not in the calamitous decline that Dominic describes(portentous voice: “life for these lads was looking a lot bleaker”). Here, Dominic’s history is seriously out of order. It is true that many of the older and less productive foundries began to close in the 1970s, but the serious years of industrial decline and mass unemployment were under the Thatcher government in the 1980s long after Black Sabbath was firmly encamped in the Los Angeles hills.

What drove young men out of traditional industry was something quite different: their own aspiration for something better. Oddly, this exact point is made by an old piece of documentary voice recording used in the programme, but which Dominic does not appear to have listened to carefully. This eyewitness makes the important point, stating “the iron trade is a dying industry … the lads leaving school now won’t entertain it, they won’t have it.” The point that the voice is making is that the young of Birmingham didn’t have to go to work in the foundries. Geezer Butler’s decision to train as an accountant is telling, his family worked in factories, he could chose not to. Prospects were not bleak for the youth of Birmingham, they were good. You could earn enough money to buy a guitar, start a band, dream of life in rock and roll band. Even if you didn’t escape you could become the manager of a cinema (as Rob Halford, lead singer of Birmingham’s Judas Priest did) or an accountant (as Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin did, although he left the course after two weeks to return to college to gain more O levels).

More importantly, Dominic entirely misunderstands (or perhaps refuses to understand) the music that members of Black Sabbath were playing from the mid-1960s. Like nearly all British bands of the period, this was not distinctively British music at all. These proto-Sabbath bands looked to US blues music (and soul too, but this was less important to the proto-Sabbath). Listening to these bands Earth, Mythology and the Polka Tulk Blues Band (you can listen to this on YouTube)[14] you can hear the movement to a heavier blues based sound that was more rock – Sabbath took it further, and revelled more in the sonic possibility of electric amplification. This was not, as Dominic opines, something “totally new”, it was built on what went before. Sabbath, unlike Led Zeppelin, did move away from blues based rock (rejecting three-chord blues forms, instead beginning to substitute unresolved tritones and Aeolian modal scales.)[15] They were, however, far from being alone in moving on blues based music at this time, the whole of progressive rock was predicated on such a move and the proto-punk movement in the USA was too.

It is difficult to say whether Sabbath were a musical evocation of industrial Birmingham, as Dominic claims. The band was, however, part of wider movement of heavier, non blues-based, rock. (Anyone who believes for a second Dominic’s assertion that heavy metal could only come from industrial Britain should listen to Bitter Creek’s 1967 song Plastic Thunder – Bitter Creek were from the US state of Georgia and show the importance of US psychedelia in the emergence of hard rock).[16]

What Sabbath represented was another step in the British musical invasion of the USA, which even in the 1970s was beginning to falter. In the early 60s the Beatles (and even more so the Stones) had taken music based on soul and blues to a white American market that had, after the initial stirrings of rock and roll, fallen back into a musical that was as racially segregated as society was. Most of the British bands that became big in the US (and from there became global stars) developed black America music, and returned it to the US market. The clearest, and most literal, example of this was Jimi Hendrix. He was brought to Britain by his British management in late 1966 where he developed his sound with a British band and had initial success in the British charts. British bands bridged black American and white American music in a way that was more difficult in the USA. Black Sabbath’s importance is that they started the process of making heavy metal less bluesy, a process that ended up with post-punk metal bands typified by Iron Maiden. But it was also a temporary state of affairs. There has been no new Beatles, and not since the new wave of British heavy metal in the 1980s (Iron Maiden, Def Leppard), no new Black Sabbath. In the US the heavy metal market has long been dominated by the US glam-metal bands such as Mötley Crüe.

Economic determinism of culture.

Dominic presents heavy metal as determined by industrial decline. This is not simply factually wrong, but shows an overly deterministic approach to culture that has much in common with crude Marxism. Dominic often fails to understand that particular social phenomena (even the bombast of heavy metal) have their own history and their development should be understood, in the first instance at least, in terms of that history. Certainly, the broader socio-economic context is an important part of this history but it tells you little about the precise form that cultural forms such as heavy metal took.

Dominic does this with art too. Dominic suggests that the emergence of the Young British Artists from 1988 was a product of the Thatcher years and the triumph of market forces, that its key backer Charles Saatchi realised that “this was art for the age of money” and “the perfect products for an age of conspicuous consumption” ..All of this is at a level of vague generality that makes it difficult to assess, but if one begins to examine the real history of Saatchi and the YBAs this simplistic narrative begins to unravel.

Saatchi, Dominic confidently tells us, “strode into the world of art at the high water mark of Thatcherism” after her third election victory in 1987. This presumably refers to Saatchi visiting the proto-YBAs Frieze exhibition in 1988, although his systematic interest in them did not start until 1991, the date when he started buying and then commissioning contemporary British art (Saatchi is no fool, the art market had collapsed in 1990 with the property market). The term “Young British Artist” was the result of Saatchi’s interest, and did not emerge until 1992, and the acronym YBA only started to be used in 1996. What this misses out was that Saatchi was already in 1991 a major art collector. However, not of British art but of American and particularly pop art, and had been an avid collector of American pop culture since he was a boy. He bought his first New York minimalist painting by Sol LeWitt in 1969 and was almost solely interested in American contemporary art until 1991 (that Saatchi, like the Beatles, had been obsessed with American pop culture does not fit in with Dominic’s narrative, so he ignores it).

While it is true that the Goldsmith’s group, who were to go on to be at the heart of the YBA movement, emerged in 1988, the YBA movement did not coalesce until around 1992 when Saatchi started setting up YBA exhibitions, and the process reached its zenith in 1997 with Sensation at the Royal Academy. The narrative of this all being about the money is, however, deeply flawed. The London art market was at this time in the doldrums. As FT’s art market correspondent Georgina Adam puts it, “In the late 1980s and early 1990s contemporary art was hardly sold at auction. While there was a brief ‘greed is good’ interlude in the 1980s – when Julian Schnabel and others enjoyed superstar status – this ended with the 1990 slump.”[17] The art market only picked up around 2004 and since then prices have spiralled. Damien Hirst put on his Frieze show of 1988 because the big-galleries were uninterested in the proto-YBA’s art, and Saatchi’s patronage in the early 1990s was important to them because no-one else supported it. Saatchi bought Hirst’s shark, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone living for, £50,000 in 1992 (he sold it for it for £6.5 million in 2004). It was not until well after 2000 that YBA art began to demand high prices.

What is clear is that the narrative about the YBAs and Saatchi that Dominic sets up makes no sense. These were not people who in the period of high Thatcherism found a ready market for their art. They toiled for years for very little reward. It was only in the mid-1990s, with Saatchi’s support, that they began to be able to sell work at all, and only around 2004 that their work attracted big bucks as the global market for contemporary art boomed. It is interesting to note that Damien Hirst’s star has waned since his boom year of 2008. Just as Andy Warhol prices collapsed as a result of overproduction, the existence of over 6,000 Damien Hirst artworks has led one analyst to call his work the sub-prime of the art world.[18] There is a story to be told about the relationship between British art, international trends in art, the art market and the British economy. But Dominic does not tell it.

This determinism is visited upon us one last time when Dominic is talking about the computer game Elite. I am not sure how important Elite was as a video game, and as with many of Dominic’s choices I feel it is more to do with what he was interested in when he was ten. I am also not sure that computer games carry much national cultural content, they all have either a Super Mario type no-place to them, or are clearly part of US pop-cultural hegemony. There is no way of guessing Tetris is Russian, Candy Crush is British or that Minecraft is Swedish (my knowledge of video games is limited, so I will happily be corrected here). So when Dominic suggests that “Elite was a product of the Thatcherite 80s, a fact reinforced by its mercenary ethos: trade, fight and pillage your way to the top…” I doubt that he is right. Games develop largely in the context of the games that precede them, and he is overstating how their context reflects the immediate social context in which they are produced.. Whatever their faults, Thatcher’s governments were little interested in military-mercantile adventurism (let alone pillaging) so the analysis is strained anyway. Elite’s roots are, I suspect, in an older form of computer gaming that did not rely on video graphic but text based choices (which go back to the very earliest computer games such as the text-based 1971 game Star Trek) and also has roots in non-computer based fantasy gaming. It would appear to me that unless these sources are understood, then it is impossible to say anything about the relationship of a game to its contemporaneous social influences.

By the end of the programme, Dominic has lost any sense of where it started (that Black Sabbath were selling a culture that could not have come from anywhere else than Britain, its socio-economic roots determine its content as uniquely British). Elsewhere in the programme he argues that J. Arthur Rank’s motivation was to create British film, and cites J Maynard Keynes (amongst other things, the founder of the Arts Council) rousing the post-war British radio audience with the imperative of “death to Hollywood”. But by the end of the programme Dominic is lauding the Grand Theft Auto series of video games. These are made in Scotland but are (as Dominic points out), culturally American. It is indicative of the intellectual and thematic mess of this programme that the theme of post-imperial British popular culture reasserting a sense of Britishness slips from view and is then contradicted. So is Britain now just exporting cultural material that may just as well be American? If this were a serious history of British popular culture, we would surely have an answer. Here, the question is not even asked.

Culture is a thing manufactured for profit.

Dominic has a rare gift for smugly stating the bleedin’ obvious while simultaneously entirely missing the point. The key case in point here is his repeated assertion that British popular culture is manufactured for profit. Of course we live in a capitalist society and cultural capitalism is like any other, it takes human creativity and subordinates it to market relations. But that popular culture is made to be sold tells us very little, directly at least, about the content of that culture. Very often the inventors, musicians and artists have to work in opposition to the market, toiling without reward or recognition for years. Thus Dominic is profoundly wrong in compounding the way culture is made within the content of that culture.

The first example that Dominic uses is J. Arthur Rank, the scion of Britain’s richest flour-milling family who became its most important film producer form the 1930s to the 1950s. Rank started with a series of acquisitions in 1935 leading to the formation of the Rank Organisation in 1937. However, Dominic is very confused here. On the one hand he states that for J Arthur Rank films were a commodity like any other, and also that he wanted distinctively British and culturally uplifting films. Both of these might have been pressures on J Arthur Rank. It is a question of carefully sifting the evidence to see how these commercial and cultural pressures played out. Certainly, the early Rank Organisation films suggest the objective was to make money. The most successful early Rank films were a series featuring the music hall star Will Hay, often playing a feckless school teacher involved in various criminal shenanigans. These films were somewhat amoral. But these are not what Dominic focuses on. Instead his sole focus is the 1945 film of Henry V. This tells us very little about J Arthur Rank. The film was not produced by the Rank Organisation but by Two Cities Films, a company set up by two Italian exiles from fascism, Filippo Del Giudice and Mario Zampi. Two Cities was interested in making films more than money, and made some of the most notable British films of the Second World War years (Freedom Radio (1940), In Which We Serve (1942) as well as two films engaged with women’s role in the war The Gentle Sex and The Lamp Still Burns (both 1943).

Thus, when Laurence Olivier began to develop the idea of a film of Henry V as a wartime morale booster it was to Two Cities that he turned. Two Cities produced the film, but turned to the Rank Organisation for money (they had worked with Rank as a distributor already). The film cost so much that Rank ended up owning Two Cities. The point is there was a tension between J Arthur Rank (who was cautious of the film and feared it would not make money) and Olivier and Del Guidice who were more interested in making something of artistic value (exactly the tension between those who wish to create culture and those who wish to sell it outlined above). It is thus highly questionable whether Henry V is the prototype for historical dramas (as the British brand) that Dominic suggests. Indeed, the Rank Organisation’s output in the 1950s was dominated by a mix of home market films, Norman Wisdom comedies beginning with Trouble in Store (1953), the Doctor films starting with Doctor in the House (1954) and war films such as The Malta Story (1953). Henry V presaged no headlong rush into costume drama, indeed the Rank Organisation had made a number of costume dramas through Gainsborough Pictures (which it had owned since 1937), but dissatisfied with the results shut the studio down in 1949.

The second example of culture as business that Dominic uses is the Beatles. He suggests the Beatles were not so much performers as business-people (a view which somewhat beggars belief given the controversy that still surrounds the consequences of handing their business affairs over to Brian Epstein until his death 1967; their lack of business acumen was then amply demonstrated by their attempt to run their own business affairs through Apple Corps). While it is true that the Beatles made a lot of money for the people involved, is this really the framework for understanding their impact? The image that Dominic presents of the Beatles as of a group of cheeky Liverpudlians enriching themselves while being willing shaped by a Svengali figure, their manager Brian Epstein. There is some small truth to this. It was Epstein who put more structure into the Beatles stage shows, and encouraged them out of denim and leather and into suits (all of this was readily accepted by McCartney, and resisted by Lennon). The suggestion, however, that in so doing he created “a sanitised exaggerated Britishness” is utter nonsense. The Beatles characteristic colourless suits were German, and their adoption was probably under the influence of Astrid Kirchherr, the Hamburg girlfriend of Stuart Sutcliffe (the Beatle’s bass player in the early 1960s). Kirchherr has been credited with their haircuts too (Sutcliffe long favoured a moptop), but she denies this suggesting that it was a common style in Germany at the time. Other items of the Beatles wardrobe in those early years were variations of mod fashion. The mod suit drew heavily on French and Italian styles, although they were usually tailored locally.[19] Their Cuban heeled boots were of US heritage, probably by way of Italy again. There was not much British about their clothing.

More importantly, the significance of the Beatles lies not in their dress sense but their music. If they had dressed like the more eclectic Rolling Stones in the early 60s (large dollops of mod mixed in with bits of jazz-beatnik and stronger US influences) would it have made that great a different? What made the Beatles stand out and last is that they were not manufactured as other bands were at that (and many were afterwards). Particularly, they chose their own repertoire and increasingly wrote their own songs (which was not common at the time for many genres of music). After their first album, Please, Please Me (1963) on which Lennon and McCartney wrote only eight of the fourteen tracks, all subsequent Beatles albums were written nearly exclusively by band members. It was because of the Beatles and singer-songwriters such as Bob Dylan that it soon became only manufactured pop-bands who had their material written for them.

It is worth emphasising that, in the early years at least, the primary influences on the Beatles music were (other than the Shadows) almost entirely American (blues, Motown, Little Richard’s falsetto shrieks, Chuck Berry’s rock and roll, and even ragtime, with some white influence of rockabilly, Elvis and especially the country-derived close vocal harmonies of the Everly Brothers). As noted above, the success of the British musical invasion if the US was the ability to be white while performing black music (while also synthesising and developing it), a knack that after Elvis joined the army many white American performers lost. Some, like the Animals and the early Stones, did this entirely by lifting (mainly) black American repertoire. The Beatles took it further by synthesising elements from different musics into something new – but it was not British in any meaningful sense.

While it would be wrong to divide the world into artistic types and business types – there are many artists who have a very strong grip on their business affairs – it is usually the case that the producers of pop culture and those who administer its business side are different people. The production side cannot, as shown above, be reduced to a business plan as Dominic suggests.

The Victorian Legacy

The last theme that Dominic develops in this programme is that British pop culture is just the most recent manifestation of a British entrepreneurial spirit stretching back to the industrial revolution and fully realised in Victorian values. In this first programme, Dominic is not (in the main) referring to the content of the pop culture, although I understand he will go on to argue that.[20] The Victorian values here are a sanitised Sunday school type version (like Thatcher’s Victorian values). Dominic’s kind of Victorian is an upstanding entrepreneur, a civic minded philanthropist, self-made man (sic), self-reliant, industrious, innovative and driven to sell and trade everything that he (sic) makes. There is certainly no hint of moral ambiguity, hypocrisy or sexual impropriety, the Victorians were simply above these things in Dominic’s universe.[21]

There is little about this particular element of Dominic’s analysis other than the assertion that British cultural entrepreneurs are very much like their Victorian counterparts. Thus, Charles Saatchi is characterised as a self-made man who bought art and set up museums, very much like Henry Tate. Ignoring that Saatchi is hardly a self-made man (his father did leave his wealth behind when he fled Iraq in 1947, but re-established his fortune in Britain through textile manufacture),[22] more importantly Saatchi is entirely unlike Tate in that he is a market maker who resells his acquisitions for profit. He bought much YBA art cheap, and sold it expensive. He may have paid around £10,000 a piece for much of Hirst’s early work; in 2006 Hirst bought twelve of these pieces back for a reported £8 million. It is undoubtedly the case that Saatchi helped to make the market in YBA art and then profited tremendously from selling some of the work. There is no comparison with Henry Tate (even though he was a Victorian, there is no evidence that he hit his much younger wife).

The comparison with the past becomes ridiculous when the young inventors of the computer game Elite are compared with the inventor of the water frame, Richard Arkwright (Arkwright, like many of the inventors cited by Dominic, is not a Victorian but a Georgian who died in 1792). Arkwright had no formal schooling, became a wig dyer before moving into textiles. His engineering was self-taught. The creators of Elite, David Braben and Ian Bell, were well educated (one privately) and were studying science and maths at Jesus College, Cambridge at the time they wrote Elite. The machine that they wrote it on was the BBC Acorn, a state subsidised machine[23] that hardly matches the classical liberal of Victorian innovation.

Another one of Dominic’s new is Andrew Lloyd Weber who is held up for being an impresario, capitalist empire builder, entertainer and producing culturally uplifting and enlightening material (no, really) just as his nineteenth century forebears did. That we still live in a world where people engage in market based activities, entrepreneurs will continue to look like entrepreneurs. One may as well say that we are just like the Victorians, we drink, eat and breathe. What one needs, at the very least, is to show that others are unlike this. But it you look at entrepreneurs in (say) the USA, they too will look very much like the Victorians under these vague criteria.

Dominic adds another dimension to his Homo Victoriani by adding the imperial element. Here he tells the story of Chris Blackwell, scion of the white colonial aristocracy in Jamaica. In the 1960s in Britain, through his Island Records label, Blackwell brought Jamaican ska to a British audience with Millie Small’s My Boy Lollipop 1964. Through the sixties, Island put out a huge quantity of ska and early reggae (rocksteady) records in the UK, but by the 1970s Island switched to a roster of artists dominated by a left-field selection of white folk-rock and progressive rock artists. Reggae concentrated on one or two acts, most notably Jimmy Cliff but after the film and album The Harder They Come Island and Cliff parted company. Thus Blackwell was looking for a new reggae star with which to break into the mainstream.

The way that Dominic tells the story is that Blackwell launched The Wailers (there was no “Bob Marley and….” until the third Island album, Natty Dread) into mainstream recognition with his first Island album, Catch a Fire. The essentials of the story are accurate, but the context in which Dominic puts this success could not be more wrong.

Dominic is wrong to say that through Bob Marley Blackwell took reggae into the mainstream. As the historian of reggae Lloyd Bradley has argued, he really only took Bob Marley into the mainstream.[24] This is not Island’s fault, in the wake of Marley’s success they reinvigorated their reggae output and put out some of the best roots albums of the 1970s, a little to dub and toasting into the bargain. Between 1974 and 1979 they released records by Burning Spear, the Lee Perry produced Upsetters, Junior Murvin and Max Romeo, Toots and Maytals, the Heptones, Dillinger, Rico, and Jah Warrior, they also put out the first releases of British reggae bands Asward and Steel Pulse. These met with little commercial success in the 1970s, although Island did have some with the louche reggae of Third World. The only sizeable white audience that reggae had in the 1970s beyond the crossover of Bob Marley were punks, the only radio play artists other than Marley received was on John Peel (it is worth remembering that Dominic thinks that there was no such thing as punk, just as he thinks that the sixties did not happen – all in tradition and continuity).

The main point, however, is Dominic’s assertion that this bringing of reggae (or at least the part represented by Bob Marley) into the mainstream “could only have happened in Britain … Blackwell .. was capitalising on the relationship between the imperial metropolis, London, and the former colony, Jamaica.” This simply is not true. The clearest evidence of this is Johnny Nash. Most people will have forgotten Nash (his biggest hit was I Can See Clearly Now but most people now think it is a Jimmy Cliff song). This is understandable, much of his material sounds pretty bland today. Nash was a black American singer with a soul background. He travelled to Jamaica (accounts differ, but it was between 1965 and 1968), worked with the Wailers and others, and recorded some rocksteady tracks. He sought to break these in the USA, which he did with considerable success. In Britain too be had success with three top ten rocksteady hits in 1968 and 1969 (they are somewhat easy listening with overdubbed strings, but the basic track is straight down the line rocksteady). In 1972 he took Bob Marley’s Stir it up into the top twenty in both USA and UK charts (despite a very odd bit of recorder on it). The follow up, Nash’s own composition I Can See Clearly Now went to number 1 in the US. Nash was the first international reggae star.

Importantly, there is a clear link between Johnny Nash and Bob Marley. Nash was managed by a black American manager, Danny Sims. In order to gain more commercial freedom Sims moved to Jamaica in 1965 (perhaps taking Nash with him). In the late 1960s Sims began to manage Marley and introduced him to a wide variety of black American music: soul, blues, jazz and Hendrix. In 1970 Nash was invited to work on a film in Sweden, and Marley went too, and the two worked together to develop a sound that would appeal to Swedish audiences. All of this, even before Blackwell, had a huge influence on broadening Marley’s sound.[25] The link with Empire is, it would seem, not as vital as Dominic suggests. Reggae spread is not the result of imperial hangover, it is the result of musicians moving around the world and learning, synthesising and playing to audiences – a heritage of colonialism is simply not necessary to do this.

Conclusion

There are many lessons here. The main one is that things have their own history. Reggae, heavy metal, the British art market, the Beatles, computer games and the musical all have their own histories. Some of these histories are contested, some have not been codified and others have poor history. It is right that historians take these histories and attempt to synthesise them into a greater whole, a rounded history that has greater reach and understanding than the small and atomistic understandings. Sadly, this is not what Dominic has done. Rather he has ignored (in large part) these histories, cherry picked parts of them to fit (what I can only assume to be) a preconceived conclusion.

Dominic concludes that we (the British) have all become storytellers. Sadly, with Dominic that is what we get, a story. A collage of historical snippets collected together to create a picture that is no longer reality, but a comforting set of myths of enduring British greatness and continuity.

[1] Dominic Sandbrook, White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties (London: Little Brown, 2006), pp200-202.

[2] Although it can be done, see Margaret Willes, The Gardens of the British Working Class Paperback (London: Yale University Press, 2014)

[3] George McKay, Radical Gardening: Politics, Idealism and Rebellion in the Garden (London: Frances Lincoln, 2012); Peter Wilson, Avant Gardening (Semiotext, 1999)

[4] Arthur Marwick, A History of the Modern British Isles 1914-1999 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), p239;, The Sixties, (Oxford: OUP, 1998); p265. “The Cultural Revolution of the Long Sixties: Voices of Reaction, Protest, and Permeation” International History Review, 27/4 (2005).

[5] For example, Tony Parsons, “Celebrate the best of British and stop sneering at Danny Boyle’s Olympics opening ceremony”, The Daily Mirror, 16th June 2012 [http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/tony-parsons-on-olympics-opening-ceremony-885199 (accessed 6/11/15)])

[6] and another For example, Patrick Sawyer, “London 2012: opening ceremony wows the Queen and the world with wit and drama”, The Daily Telegraph, 28th July 2012 [http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/olympics/london-2012/9434274/London-2012-opening-ceremony-wows-the-Queen-and-the-world-with-wit-and-drama.html (accessed 6/11/15)]

[7] Frank Cottrell Boyce, “London 2012: opening ceremony saw all our mad dreams come true”, The Guardian [online] 30th July 2012 [http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jul/29/frank-cottrell-boyce-olympics-opening-ceremony (accessed 7/11/2015)] (The print version of this was, I think, in The Observer]

[8] BIS, BIS Economics Paper No. 17: UK trade performance across markets and sectors (London; BIS, February, 2012), p83. [https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32475/12-579-uk-trade-performance-markets-and-sectors.pdf (accessed 7/11/15)]

[9] Ref needed

[10] ONS, UK Trade in Goods Analysed in Terms of Industry, Q4 2013 [http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-323524 (accessed 7/11/15)]. Also see Department of Culture, Media and Sport, Creative Industries Economic Estimates

January 2014 Statistical Release (London DCMS, 2014), P21 [https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271008/Creative_Industries_Economic_Estimates_-_January_2014.pdf (accessed 7/10/2015)]

[11] BIS, BIS Economics Paper No. 17: UK trade performance across markets and sectors (London; BIS, February, 2012), p86 {https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32475/12-579-uk-trade-performance-markets-and-sectors.pdf (accessed 7/11/2015)

[12] BIS, BIS Economics Paper No. 17, p84.

[13] Tom Norton, Five minutes with: Geezer Butler, 2014 [http://www.digitalproductionme.com/article-7406-exclusive–five-minutes-with-geezer-butler (accessed 7/11/15)

[14] Mythology (1968) doing a very standard blues workout can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pFNBDmdDdo; Earth (1969) can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL2BFC1B05F07C0345

[15] Andrew L Cope, Birmingham: The Cradle of All Things Heavy:, Black Sabbath and the rise of heavy metal music (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010) pp19-21. If you listen to the opening eponymous track on Sabbath’s equally eponymous album you can here this in full other worldly effect.

[16] Can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYqvyxK3Qpo

[17] Georgina Adam, “How long can the art market boom last?”, Financial Times 6th June 2014 [http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/9f4fff3c-eb27-11e3-bab6-00144feabdc0.html (accessed 9/11/15)] For a fuller picture of the rise of the art market see her Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market in the 21st Century (Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013)

[18] Julian Spalding, Con Art – Why you ought to sell your Damien Hirsts while you can (self published e-book: 2012, 2nd edition).

[19] Melissa M. Casburn, A Concise History of the British Mod Movement (n.d.), [http://www.gbacg.org/costume-resources/original/articles/mods.pdf]. Also see Richard Weight, Mod! A very British Style (London: Bodley Head, 2013): From Bebop to Britpop, Britain’s Biggest Youth Movement (

[20] There is a question in my mind about why there is no mention of Aleister Crowley, who although he lived to 1947 was thoroughly rooted in a Victorian esotericism and belief in the paranormal, maybe because Crowley’s heroin addition, sexual appetites and malevolence fit poorly with Dominic’s view of the Victorian legacy, but there he is on the front cover of the Beatle’s Sgt. Peppers, and was also a huge influence of Black Sabbath

[21] For a more accurate picture see, for example, Judith R. Walkowitz , City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives Of Sexual Danger In Late-Victorian London (London: Virago, 1992).

[22] Thank to @SiBarberPhoto for this nugget.

[23] Thanks to @martinmcgrath for pointing this out.

[24] Lloyd Bradley, Bass Culture: When Reggae was King (London: Viking, 2000), pp396-398

[25] Bradley, Bass Culture, pp403-408.

Question: there has been a sizeable spike in views on the site in the last couple of days, but why? . This is usually caused by Dominic having a new programme on TV, but if this is the case now I have missed it. The only explanation that I can come up with is that Alexi Sayle is currently venting some righteous spleen over Dominic’s work on the Fringe at Edinburgh. For the record, I have a great deal of admiration for Alexi’s work, and view his Stalin Ate my Homework and Thatcher Stole My Trousers as works of contemporary British history vastly greater in insight and accuracy than thinly veiled Thatcherite apologia that Dominic produces.

Question: there has been a sizeable spike in views on the site in the last couple of days, but why? . This is usually caused by Dominic having a new programme on TV, but if this is the case now I have missed it. The only explanation that I can come up with is that Alexi Sayle is currently venting some righteous spleen over Dominic’s work on the Fringe at Edinburgh. For the record, I have a great deal of admiration for Alexi’s work, and view his Stalin Ate my Homework and Thatcher Stole My Trousers as works of contemporary British history vastly greater in insight and accuracy than thinly veiled Thatcherite apologia that Dominic produces.

A review of Tomorrow World’s: An Unearthly History. Part 4 – Time (first broadcast BBC2, 13th December 2014).

A review of Tomorrow World’s: An Unearthly History. Part 4 – Time (first broadcast BBC2, 13th December 2014).